THIS is what a stolen election looks like

Twenty years ago, a combination of Black voter disenfranchisement, nepotistic partisanship, and a flawed ruling by a conflict-ridden Supreme Court handed the presidency to George W. Bush.

As President Donald Trump rages on Twitter and thousands of his sometimes dangerous dead-enders take to the streets to “STOP THE STEAL”—even as court after court rejects every one of Trump’s legal challenges and the Electoral College convenes to officially declare Joe Biden the next president of the United States—a most ignominious anniversary has passed all but unnoticed. On December 13, 2000, Vice President Al Gore conceded defeat to Texas Gov. George W. Bush after a protracted recount and legal battle lasting 36 agonizing days.

Polite historians call it “one of the most controversial presidential elections in U.S. history.” But “controversial” doesn’t begin to do justice to what happened 20 years ago. Unlike the 2020 election—which was really quite normal in every way except for the fact that Trump was on the ballot—the 2000 contest can, without hyperbole, rightfully be called stolen.

The theft happened on three fronts, all of them concerning Florida. First, state officials led by Bush’s brother disenfranchised enough Black voters to demonstrably alter the outcome of the contest. Second, Florida election authorities under the direction of Bush’s campaign co-chair moved to quash recounts lest Gore emerge victorious. Finally—and fatally—a U.S. Supreme Court dominated by Republicans and plagued by conflicts of interest intervened in what could and should have remained a state matter in order to halt a court-ordered recount, thus handing Bush a victory that could at best be called premature and at worst, fraudulent.

Let’s take a look at how it all unfolded.

Too close to call

On November 8, 2000, Americans woke up to the unusual news that the winner of the previous day’s presidential election still could not be determined. Gore had won the national popular vote by more than half a million votes over Bush. But this being the United States, that was of no consequence since presidential elections are, to many a newly naturalized citizen’s bewilderment, decided not by the people but rather by that most arcane remnant of Southern slaveowner power, the Electoral College.

Florida and a handful of smaller states remained too close to call deep into Tuesday night, although most cable and network newscasts did wrongly call the contest—not once, but twice.

By Wednesday morning, it was apparent that Florida’s 25 electoral votes would decide who would be the 43rd president of the United States. While Gore led Bush nationwide by four electoral votes—250-246—with 270 needed for the win, the governor clung to a tenuous and unofficial 1,784-vote, or 0.03 percent lead, in the Sunshine State. Florida law mandates a machine recount for any lead of less than 0.5 percent.

At the risk of playing spoiler for those who don’t know how this story ends, it should be stressed that when all was said and done, Bush would ultimately “win” the presidency by just 537 Florida votes. Keep this in mind as you read on.

Blackout

In 2000, Florida was one of only three states that permanently prohibited ex-felons from voting. During that year’s election, at least 139,000 Black Floridians—who overwhelmingly back Democratic candidates—were barred from the ballot box due to prior felony convictions, a state restriction with racist origins in Reconstruction-era efforts to disenfranchise recently-emancipated slaves. By the time Bush’s little brother Jeb was elected governor of Florida in 1999, over two decades of mass incarceration fueled by the War on Drugs meant that one in five Black voting-age Floridians was ineligible to vote. A 1998 study by Human Rights Watch and the Sentencing Project concluded the figure was closer to one in three, or more than 200,000 potential Black voters.

A large percentage of those who could not vote had been incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses, belying the structural racism of a system in which “more than 13 percent of black men—some 1.4 million nationwide—are disenfranchised for many years, sometimes for life, a result of felony convictions, many for… the same drugs that Al Gore smoked and George W. snorted in years gone by,” as University of New Mexico law professor Tim Canova observed at the time.

Republicans argued that like it or not, the law is the law. This is true and following the law, however odious it may be, should not be conflated with stealing an election. To be clear, the theft did not involve people who were not allowed to vote under the law. It involved people who were allowed to vote under the law but were prevented from doing so. And the law did also play a part in the process, as did the widespread racist intimidation, including police checkpoints and interrogations, targeting Black Florida voters. What should and will be submitted here as conclusive evidence that Bush “won” Florida due to Black voter disenfranchisement are the actions of a cabal of Bush loyalists in state government, including not just the eventual president’s governor-brother but also the secretary of state—the chief elections official—who just happened to be George W. Bush’s Florida campaign co-chair.

These gross conflicts of interests all but guaranteed a rigged process. At a 2001 hearing before the United States Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR), employees of Database Technologies, a Boca Raton firm contracted by the Florida Division of Elections to compile a list of possible felons who could be purged from the state’s voter rolls in the wake of a scandalous Miami mayoral race, testified that Emmett “Bucky” Mitchell IV, a senior attorney in the state elections office, ordered the company to make the potential no-vote list as lengthy as possible. Even after being notified that such a broad search could result in false positives, Mitchell insisted on gleaning “more names that possibly aren’t matches” and then leaving the final determination to state officials.

The Florida NAACP, along with the ACLU and other civil rights groups, sued the state following the election for violating the Voting Rights Act. During the course of the lawsuit it was revealed that 12,000 Florida voters were wrongfully purged as false felons. Edward Hailes, general counsel for the USCCR, determined that 4,752 Black Gore voters—nearly nine times Bush’s 537-vote “victory”—were thusly disenfranchised in the state. Hailes told the Nation in 2015 that the omission of so many Black voters “was outcome-determinative” in the state, and therefore the national, election.

To repeat, the chief lawyer of an independent federal agency is on record asserting that state suppression of thousands of Black votes altered the outcome of the 2000 presidential election. Trump and his dead-enders could only dream of such legitimization of their baseless blathering about election theft.

There’s more. More than 2,000 former felons from other states whose voting rights had been restored under those states’ laws were disenfranchised again when they moved to Florida. These ex-offenders then had to petition Jeb Bush to restore their rights, setting up a scenario in which a Republican governor who was also the brother of a Republican candidate for president had the power to decide the the fate of the franchise of Black people whom he knew would almost certainly vote Democrat.

Nepotism was coupled with conflict of interest in the person of Florida Secretary of State Katherine Harris, also a Republican and, critically, state co-chair of Bush’s presidential campaign. Harris would repeatedly thumb the proverbial scale in favor of Bush over the coming weeks, as we shall soon see.

Recount drama

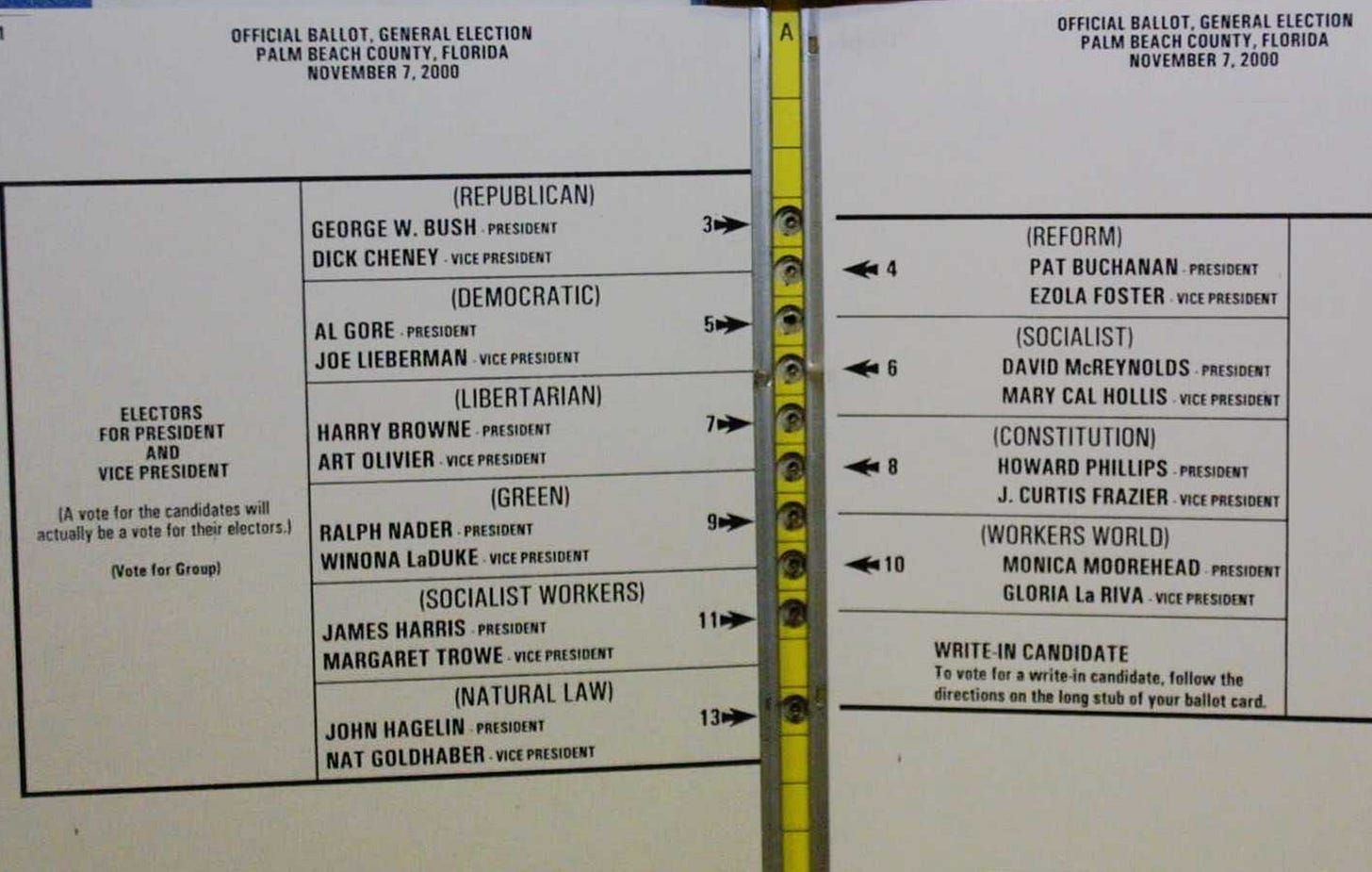

Asserting that the “integrity of our democracy” was at stake, Gore made the political calculation on November 11 to request a manual recount in four heavily Democratic Florida counties. As the recount unfolded with drama over dimpled, pregnant, and hanging chads, butterfly and caterpillar ballots, write-in votes, over-counts, under-counts, and a bewildering barrage of strange new terms, Republicans launched a misinformation campaign meant to discredit the process, while also unsuccessfully suing to stop it so that Bush could be declared the winner.

Under Florida law, all counties had to certify and report their results, including recounts, by November 14. With Bush ahead by 300 votes a week after Election Day, a state judge upheld the deadline but also ruled that further recounts could be considered. The following few days were marked by political and legal brinkmanship culminating in a November 17 state Supreme Court intervention blocking Harris from halting manual recounts until an appeal by the Gore campaign could be considered.

Bush’s lead grew to 930 votes on November 18 after overseas absentee ballots were counted. However, this was a most problematic undertaking, as Republican pressure to count as many of these ballots as possible—because many were cast by U.S. troops—resulted in the official tallying of 680 questionable votes. Some were missing postmarks or required signatures, others were postmarked too late or from within the United States, and some were even from people who had voted twice. While it is impossible to know for whom these invalid votes were cast, four out of five were accepted in counties won by Bush.

On November 21, the Florida Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the results of the manual recounts in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties must be included in the final state tally and gave the three counties five days to certify their results. The next day, as Bush’s legal team appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, the GOP flew hundreds of paid operatives into Florida to harass and intimidate Miami-Dade officials doing their best to complete the recount before the court-ordered November 26 deadline. The infamous “Brooks Brothers Riot” was organized and led by a pair of high-powered lobbyists, Matt Schlapp and self-described “dirty trickster” and future seven-count felon Roger Stone. Calling it a “riot” is no overstatement—sheriff’s deputies restored order after numerous people were beaten, kicked, and trampled as protesters tried to barge into the county election supervisor’s office while chanting “STOP THE COUNT!” Sound familiar? Instead of being punished, many of the perpetrators were rewarded with Bush administration jobs.

That same day, Miami-Dade election officials called off their recount. “We scared the crap out of them when we descended on them,” Bush campaign operative Brad Blakeman later crowed. Joe Geller, the county Democratic Party chairman who was assaulted during the fracas, later lamented how “violence, fear, and physical intimidation affected the outcome of a lawful elections process.”

But violence, fear, and intimidation do not constitute a stolen election, at least not in this case. For that, we must now turn to a much higher authority than the Miami-Dade County Board of Elections.

A conflicted court

On November 23, the Florida Supreme Court denied Gore’s request to resume the Miami-Dade recount. Three days later, Harris declared Bush the winner in Florida by 537 votes, even though there were counties still tallying ballots. Gore sued to contest the result and to force recounts where he thought he could win. A state circuit court rejected Gore’s request, but the Florida Supreme Court reversed the decision. The stage was set for what was arguably the most notorious SCOTUS ruling of our time.

Bush’s all-star legal team in Bush v. Gore included former secretary of state James Baker; future U.S. Supreme Court justices John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett; former assistant attorney general Ted Olson—who would later emerge as an unlikely champion of LGBTQ marriage equality—and a 29-year-old Ted Cruz, a former law clerk for then-U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Gore’s lawyers were led by Warren Christopher, who had served as secretary of state earlier during the Clinton administration. The Gore team was overmatched, but that is of minor import to our story.

In Bush v. Gore, the justices ruled in a 7-2 per curiam opinion that Florida’s court-ordered recount must be stopped on equal protection grounds, and 5-4 that there was no other way to recount all of the contested votes in a timely manner. The latter ruling effectively ended all recounts. It was the first time in U.S. history that the Supreme Court decided who the nation’s next president would be.

Four of the five conservative justices who voted in Bush’s favor were accused of having conflicts of interest. Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor were both septuagenarians who had stated their desire to retire during a Republican presidency. According to Newsweek, when O’Connor—who was attending an election night D.C. dinner party—heard CBS News anchor Dan Rather erroneously claim that Gore had won Florida, she uncharacteristically blurted out “this is terrible!” After O’Connor got up from her table to get a plate of food, her husband John explained that she was upset “because she was hoping to retire” in Arizona after her replacement was chosen by a Republican president and now they’d have to wait at least four more years for that.

Then there was Virginia Lamp Thomas, wife of Justice Clarence Thomas, who solicited resumes for positions in the presumptive Bush administration while Bush v. Gore was being argued. Justice Antonin Scalia’s son John worked at a law firm representing Bush in the Florida recount saga. Another of his sons, Eugene, was a partner in a firm representing Bush—in Bush v. Gore. And after Bush won and took office he nominated Eugene Scalia for U.S. labor solicitor. Today he is Trump’s labor secretary.

Despite a federal law requiring a justice to "disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned,” Scalia, Thomas, and O’Connor did not step aside. Neither Scalia nor Thomas even bothered to disclose their conflicts of interest, which surely would lead any reasonable observer to question their impartiality.

Furthermore, the justices declared without a hint of shame that their opinion was a one-time-only deal, “limited to the present circumstances.” As legal scholar Jeffrey Rosen wrote in his blistering excoriation of the unprecedented ruling, “the majority asks us not to worry about the implications of its new constitutional violation.”

Bush v. Gore strains credulity in so many ways, but perhaps none more so than in the Olympic feats of mental gymnastics it demands that we execute in order to accept that the conservative majority truly believed that states did not have the right to control their own elections. These ardent states’ rights supporters, after all, had in recent years ruled that the federal government had no right to tell states they could ban guns in school zones, or invoke the equal protection clause to compel states to protect women from violence, to name but two glaring examples.

In his stirring dissent in Bush v. Gore, Justice John Paul Stevens—joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and David Souter—presciently noted that “although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the nation’s confidence in the judges as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.”

Prominent jurists fiercely denounced the court’s decision. Harvard professor Alan Dershowitz accused the “dishonest” majority of “trying to hide their bias behind plausible legal arguments that they never would have put forward had the shoe been on the other foot.” His Harvard colleague Randall Kennedy said the five justices “acted in bad faith and with partisan prejudice.” Renowned former prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi blasted the “brazen, shameless majority” as “criminals in the very truest sense of the word.” New York University law professor Anthony Amsterdam accused them of “sickening hypocrisy.” George Washington University Law professor Jeffrey Rosen called them “Republican larcenists… who arranged to suppress the truth about the vote in Florida and thereby make off with the election of 2000.”

Getting over it

A spent but stoic Gore surrendered on December 13, conceding the presidency to Bush, “for the sake of our unity as a people and the strength of our democracy.” However, his capitulation demonstrated the opposite of democratic strength, just as Trump’s refusal to concede as I write these words—on December 13, 2020—casts a similarly dark shadow over American democracy.

Justice Stevens was right. Bush v. Gore did erode public trust in the nation’s highest court and its role as impartial arbiter—some say irreparably. When asked about the conflicts and inconsistencies in the case, Scalia, who died in 2016, would invariably reply “get over it”—a shockingly flippant admonition that was later affectionately borrowed by everyone’s favorite liberal justice and Bush v. Gore dissenter, the Notorious RBG.

Despite what numerous eminent observers called a “rigged” or “stolen election” and even a “constitutional coup,” it seems most Americans heeded Scalia’s advice. No angry crowds took to the streets chanting “STOP THE STEAL!” Instead, they took to their couches to watch Survivor and Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.

Meanwhile, the Democrat blame game was played in earnest. First and foremost, liberals blamed Green Party candidate Ralph Nader, despite the fact that seven other candidates also received more votes in Florida than Bush’s 537-vote margin of “victory.” They did not blame the 12 percent of registered Florida Democrats—some 308,000 voters—who cast ballots for Bush. And they would never dream of blaming the Democratic Party for fielding candidates like Gore who supported the same wars and the same corporations as Republicans, but with the added hypocrisy of feigning to give a damn about the working people crushed by their thoroughly bipartisan neoliberalism. The Democrats apparently learned little, as 2016—and nearly 2020—showed.

An inconvenient truth

There have been numerous exhaustive postmortems of the 2000 Florida recount. Some show Gore would have won, others Bush, depending on which of the dizzying permutations and metrics are employed. Some say Gore’s failure to request a statewide recount was a fatal mistake. Others argue that ballot errors committed by thousands of Democratic voters cost him the election. Still others assert badly-designed ballots doomed the vice president. It is frankly next to impossible to discern who would have emerged victorious if one tries to make sense of all of these wildly disparate situations and studies.

However, too few of the postmortems factored in the thousands of wrongfully disenfranchised Black Floridians who, if allowed to exercise their right free of suppression, would undoubtedly have proven “outcome-determinative,” to quote the federal attorney Hailes. Sadly, Gore failed to support disenfranchised Blacks in their legal battles, or even protest in any way what Rep. Charles Rangel (D-N.Y.) at the time called “the greatest mass disenfranchisement of African Americans since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”

Ultimately, we cannot discuss disenfranchisement without an honest examination of Democrats’ role in expanding the prison-industrial complex in the 1990s. While the roots of mass incarceration can be traced back a full century before Richard Nixon declared war on drugs in 1971, and while Ronald Reagan is deservedly the president most associated with escalating that war and with overseeing a 115 percent surge in incarceration, under Bill Clinton—Gore’s boss—the U.S. adult prison population rose from 851,000 in 1992 to more than 1.4 million in 2001, a 64 percent increase.

It was during the Clinton/Gore administration that the now-infamous 1994 crime bill, co-authored by Joe “lock the S.O.B.s up” Biden, was passed and was followed by more prisons, more prisoners, and harsher sentencing. And with Black Americans incarcerated at seven times the rate of whites in the 1990s, it is an inconvenient truth that a considerable part of the blame for a good chunk of those “outcome-determinative” disenfranchised Black voters who cost Gore the election falls squarely on the very administration in which he served, as well as on all of the other “tough on crime” Democrats like Joes Lieberman and Biden.

As the eminent academic Noam Chomsky observed shortly after the 2000 election, the policies of the Clinton/Gore administration ended up “disenfranchising their own voters.”

Nevertheless, it was this disenfranchisement—at once intimately intertwined with yet separate from efforts by nepotistic Florida officials to prematurely halt the counting of legitimate ballots—and a conflicted, partisan Supreme Court, that together constitute the stolen election of 2000. Trump’s desperate, flailing attempt to convince anyone but the die-hard supporters he must have had in mind when he boasted that he could “stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and not lose voters” that the 2020 presidential election was “the most corrupt in U.S. history” may just be the most grotesquely preposterous lie of his presidency. And that’s saying a lot.

Brett Wilkins is a staff writer for Common Dreams and a member of Collective 20. www.brettwilkins.com